Biological profile

The Skeleton-ID mini-guides have been created for quick reference of the methods while working in the ‘Data Analysis’ section of the Biological Profile module. They are a tool to facilitate and speed up the workflow within the software.

These methods were developed by different authors, and the original publications are referenced throughout. Their consultation is encouraged in case of any doubt.

Hip-bone morphometric method for Sex Estimation

Murail's method [1], formally known as the Probabilistic Sex Diagnosis (DSP because of its acronym in French), offers a revolutionary approach to sex determination using hip-bone measurements. This tool is based on a comprehensive database encompassing over 2,040 adult specimens from diverse populations across the globe. Unlike traditional methods that often rely on visual assessments, DSP utilizes a set of ten morphometric variables to compute the probability of a specimen being male or female. This quantitative approach minimizes subjectivity and allows for accurate sex determination even when the hip bone is partially preserved.

The authors first wanted to validate the hypothesis that all different populations of modern humans share a common pattern of sexual dimorphism in hip bones. To do this, they studied reference samples from four geographical areas: Europe, Africa, North America, and Asia, including one to three subgroups from each. Developed by Pascal Murail and colleagues, DSP acknowledges the inherent variability in pelvic bone morphology among different populations, making it universally applicable. This method is particularly valuable in forensic anthropology and archaeology, where precise sex estimation can significantly influence the results of an identification process or the interpretation of sociocultural aspects of past populations.

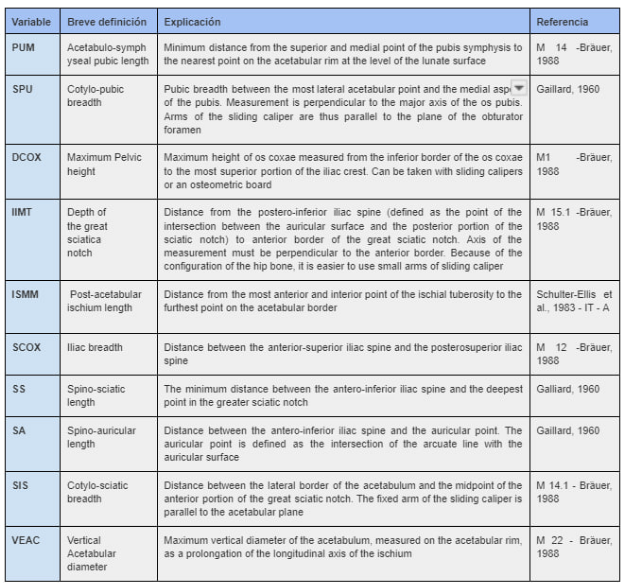

Table 1: Variables description, Murail 2005.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics (by sex) for the os coxae variables in the metapopulation reference sample. N = sample size; sd= standard deviation; F - females, M - males. The last column gives the p-value of a t-test for the comparison of means between sexes

The method is available in Skeleton-ID’s Biological Profile module, facilitating its application in both academic research and practical forensic applications. The user only needs to introduce the measurements requested by the method and the software will provide the sex estimation, ensuring accurate results and reducing human error. Note: there is now a DSP2 [2] by the official team.

REFERENCES

[1] Murail, P., Brůžek, J., Houët, F., & Cunha, E. (2005). DSP: a tool for probabilistic sex diagnosis using worldwide variability in hip-bone measurements. Bulletins et mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris. BMSAP, 17(17 (3-4), 167-176.

[2] Brůžek, J., Santos, F., Dutailly, B., Murail, P., & Cunha, E. (2017). Validation and reliability of the sex estimation of the human os coxae using freely available DSP2 software for bioarchaeology and forensic anthropology. American journal of physical anthropology, 164(2), 440–449. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.23282

Pubic symphysis morphoscopic method for Age Estimation

The Suchey-Brooks Method [3] is a significant advancement in skeletal age determination, focusing on the pubic symphysis to estimate age at death. Developed by Dr. Judy Suchey and Dr. Douglas Brooks, this method categorizes the pubic bone into six phases based on morphological changes observed through the progression of life. It emerged from an extensive study involving over 1,200 specimens with documented ages, in Los Angeles (USA). Among them, 739 were male and 273 were female, ranging in age from 14 to 99 years, from a representative sample of the reference population, providing a robust framework for accurate age estimation.

This method is particularly noted for its detailed phase descriptions, which include changes in the ventral rampart, symphyseal face, and dorsal plateau. Each phase corresponds to a specific age range, refined through extensive empirical research. The Suchey-Brooks system is praised for its precision and reliability, and it has been widely adopted in both forensic and archaeological settings. Here are the descriptions of the different phases:

- Phase 1: The symphyseal face has a billowing surface (ridges and furrows) extending up to the pubic tubercle. The horizontal ridges are well-marked and ventral beveling may be commencing. Although ossific nodules may occur on the upper extremity, a key to the recognition of this phase is the lack of delimitation of either extremity (upper or lower).

- Phase 2: The symphyseal face may still show ridge development. The face has commencing delimitation of lower and/or upper extremities occurring with or without ossific nodules. The ventral rampart may be in beginning phases as an extension of the bony activity at either or both extremities.

- Phase 3: Symphyseal face shows lower extremity and ventral rampart in process of completion. There can be a continuation of fusing ossific nodules forming the upper extremity and along the ventral border. The symphyseal face is smooth or can continue to show distinct ridges. The dorsal plateau is complete. Absence of lipping of symphyseal dorsal margin; no bony ligamentous outgrowths.

- Phase 4: Symphyseal face is generally fine-grained although remnants of the old ridge and furrow system may still remain. Usually, the oval outline is complete at this stage, but a hiatus can occur in the upper ventral rim. The pubic tubercle is fully separated from the symphyseal face by the definition of the upper extremity. The symphyseal face may have a distinct rim. Ventrally, bony ligamentous outgrowths may occur on the inferior portion of pubic bone adjacent to the symphyseal face. If any lipping occurs, it will be slight and located on the dorsal border.

- Phase 5: Symphyseal face is completely rimmed with some slight depression of the face itself, relative to the rim. Moderate lipping is usually found on the dorsal border with more prominent ligamentous outgrowths on the ventral border. There is little or no rim erosion. Breakdown may occur on the superior ventral border.

- Phase 6: Symphyseal face may show ongoing depression as the rim erodes. Ventral ligamentous attachments are marked. In many individuals, the pubic tubercle appears as a separate bony knob. The face may be pitted or porous, giving an appearance of disfigurement with the ongoing process of erratic ossification. Crenulations may occur. The shape of the face is often irregular at this stage.

The description of each of the phases applies to both male and female individuals.

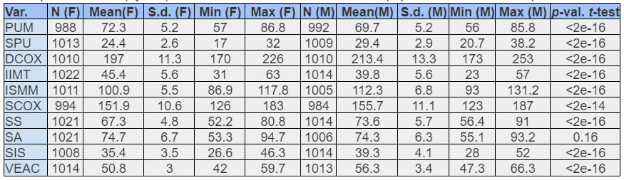

Table 3: Age ranges for each phase [3]

The Suchey-Brooks Method's utility extends beyond mere academic interest; it plays a crucial role in legal contexts where age determination can influence the outcome of investigations. Its development also highlighted the need for accurate documentation in skeletal collections, prompting improvements in how such data are collected and analyzed.

This method is available in Skeleton-ID’s Biological Profile module, where the expert can select the sex and phase of the specimen under analysis and the software will provide an estimation of the age.

REFERENCES

[3] Brooks, S. & Suchey, S. (1990). Skeletal age determination based on the os pubis: a comparison of the Acsádi-Nemeskéri and Suchey-Brooks methods, Hum. Evol., vol. 5, pp. 227–238.

Morphometric method for Height Estimation

Developed by Maria Cristina Mendonça, this method provides a systematic approach to estimating human stature from the lengths of long bones [4], a critical aspect of forensic anthropology. Mendonça's method is based on her doctoral research, which analyzed a vast array of long bones to create regression formulas capable of predicting an individual's height with a high degree of accuracy.

To carry out the study, 200 cadavers were selected from the Institute of Legal Medicine of Porto (IMLO), 100 males and 100 females, mostly from the northern region of Portugal aged between 20 and 59 years.

The method employs mathematical models that correlate specific long bone measurements (e.g., femur, humerus) with stature, taking into account variations due to age, sex, and population differences. This approach is grounded in extensive empirical data, enhancing its reliability and precision compared to earlier techniques.

The regression formulas used are as follows:

Females:

- [64.26 + 0.3065 * Maximum length of humerus] ± 7.70

- [55.63 + 0.2428 * Physiological length of femur] ± 5.92

- [57.86 + 0.2359 * Maximum femur length] ± 5.96

Males:

- [59.41 + 0.3269 * Maximum humerus length] ± 8.44

- [47.18 + 0.2663 * Physiological length of the femur] ± 6.90

- [46.89 + 0.2657 * Maximum length of femur] ± 6.96

Mendonça’s method has practical applications in both forensic and archaeological scenarios, where determining the stature of individuals can provide insights into demographic patterns, health status, and social hierarchies of historical populations. Its development marks a significant contribution to the field, enabling more detailed and accurate reconstructions of past lives. It’s available in Skeleton-ID’s Biological Profile module, where the user can input measurements of long bones and get a height range for any individual.

REFERENCES

[4] Mendonça, M.C. (1998). Contribución para la identificación humana a partir del estudio de las estructuras óseas: Determinación de la talla a través de la longitud de los huesos largos, Tesis Doctoral, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Facultad de Medicina, Madrid.

Rib morphoscopic method for Age Estimation

The Skeleton-ID Biological Profile module incorporates a sophisticated age estimation tool based on rib morphoscopic analysis [5, 6], which is invaluable in forensic and anthropological investigations. The analysis focuses on observable traits at the sternal end of the fourth rib, which undergo distinct transformations with age. Iscan and Loth studied the metamorphosis of the external end of the fourth rib in fourth ribs of individuals of known age and sex (two separate samples of over 100 individuals divided by sex). They examined the shape and texture of the sternal end and defined a series of distinct phases based on morphological changes at the costochondral junction. These phases are further nuanced for males and females due to differential aging patterns influenced by biological variations.

Here are the phases they defined for males:

- Phase 0. The articular surface is flat or gently undulating with a regular, rounded edge. The bone is smooth, firm, and very solid (Plate 1: Fig. 0a, b, and c).

- Phase 1. The beginning of amorphous cleavage appears on the articular surface, some of the undulations may be preserved. The rim is rounded and regular. In some cases, scalloping may begin to be seen at the edge. The bone remains firm, smooth, and solid (Plate 1: Fig. 1a, b and c).

- Phase 2. The fossa is deeper and more angulated, in a V-shape formed by the anterior and posterior walls. The walls are thick and smooth, slightly wavy or scalloped towards the end, but with rounded edges. The bone is firm and solid (Plate 1: Fig. 2a, b and c).

- Phase 3. The deepening fossa changes from being narrow to a more moderate U-shape. The walls remain fairly thick, with rounded edges. Some scalloping may be retained, but the rim becomes more irregular. The bone remains fairly firm and solid (Plate 2: Fig. 3a, b and c).

- Phase 4. The depth of the fossa increases, but the shape remains a narrow-moderate U-shape. The walls are thinner, but the ends remain rounded. The rim is more irregular, with no trace of the scalloped pattern. There is some decrease in the weight and firmness of the bone, but despite this, the overall quality of the bone is maintained (Plate 2: Fig. 4a, b and c).

- Phase 5. There is hardly any increase in the depth of the fossa, but at this stage, the shape becomes predominantly open U-shaped. Walls show further thinning and edges begin to taper. Increasing irregularity towards the rim. None of the scalloped pattern remains, which has been replaced by irregular bony projections. The bone remains in relatively good condition, but signs of deterioration appear with evidence of porosity and loss of density (Plate 2: Fig. 5a, b, and c).

- Phase 6. The pit is remarkably deep and broad U-shaped. The walls are thin and the edges are sharp. The rim is irregular and shows bony projections of considerable size, often more pronounced at the lower and upper edges. The bone is noticeably lighter, thinner, and porous, especially in the interior of the fossa (Plate 3: Fig. 6a, b, and c).

- Phase 7. The fossa appears deep and U-shaped wide. The walls are thin and fragile and show irregular, sharp edges with bony projections. The bone is light and brittle and its quality is significantly deteriorated, showing evident porosity (Plate 3: Fig. 7a, b, and c).

- Phase 8. In the final stage, the pit is very deep and wide. In some cases, the base of the pit is absent or filled with bony projections. The walls are extremely thin, fragile, and brittle, with sharp, sharply irregular edges and bony projections. The bone is very light, very thin, brittle, fragile and porous. Window formations may appear on the walls (Plate 3: Fig. 8a, b, and c).

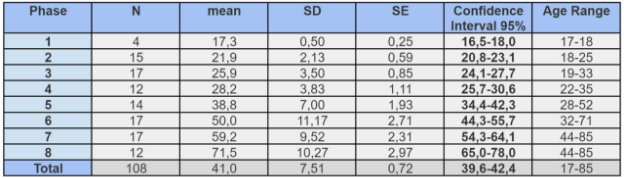

Table 4: Descriptive statistics of phases (males)

The phases defined for female individuals are as follows:

- Phase 0. The articular surface is nearly flat with ridges or billowing. The outer surface of the sternal extremity of the rib is bordered by what appears to be an overlay of bone. The rim is regular with rounded edges, and the bones itself is firm, smooth, and very solid.

- Phase 1. A beginning, amorphous indentation can be seen in the articular surface. Ridges or billowing may still be present. The rim is rounded and regular with a little waviness in some cases. The bone remains solid, firm, and smooth.

- Phase 2. The pit is considerably deeper and has assumed a V-shape between the thick, smooth anterior and posterior walls. Some ridges or billowing may still remain inside the pit. The rim is wavy with some scallops beginning to form at the rounded edge. The bone itself is firm and solid.

- Phase 3. There is only slight if any increase in pit depth, but the V-shape is wider, sometimes approaching a narrow U as the walls become a bit thinner. The still rounded edges now show a pronounced, regular scalloping pattern. At this stage, the anterior or posterior walls or both may first start to exhibit a central, semicircular arc of bone. The rib is firm and solid.

- Phase 4. There is a noticeable increase in the depth of the pit, which now has a wide V- or narrow U-shape with, at times, flared edges. The walls are thinner but the rim remains rounded. Some scalloping is still present, along with the central arc; however, the scallops are not as well defined and the edges look somewhat worn down. The quality of the bone is fairly good but there is some decrease in density and firmness.

- Phase 5. The depth of the pit stays about the same, but the thinning walls are flaring into a wider V- or U-shape. In most cases, a smooth, hard, plaque-like deposit lines at least part of the pit. No regular scalloping pattern remains and the edge is beginning to sharpen. The rim is becoming more irregular, but the central arc is still the most prominent projection. The bone is noticeably lighter in weight, density and firmness. The texture is somewhat brittle.

- Phase 6. An increase in pit depth is again noted, and its V- or U-shape has widened again because of pronounced flaring at the end. The plaque-like deposit may still appear but is rougher and more porous. The walls are quite thin with sharp edges and an irregular rim. The central arc is less obvious and, in many cases, sharp points project from the rim of the sternal extremity. The bone itself is fairly thin and brittle with some signs of deterioration.

- Phase 7. In this phase, the depth of the predominantly flared U-shaped pit not only shows no increase, but actually decreases slightly. Irregular bony growths are often seen extruding from the interior of the pit. The central arc is still present in most cases but is now accompanied by pointed projections, often at the superior and inferior borders, yet may be evidenced anywhere around the rim. The very thin walls have irregular rims with sharp edges. The bone is very light, thin, brittle, and fragile, with deterioration most noticeable inside the pit.

- Phase 8. The floor of the U-shaped pit in this final phase is relatively shallow, badly deteriorated, or completely eroded. Sometimes it is filled with bony growths. The central arc is barely recognizable. The extremely thin, fragile walls have highly irregular rims with very sharp edges, and often fairly long projections of bone at the inferior and superior borders, "Window" formation sometimes occurs in the walls. The bone itself is in poor condition--extremely thin, light in weight, brittle, and fragile.

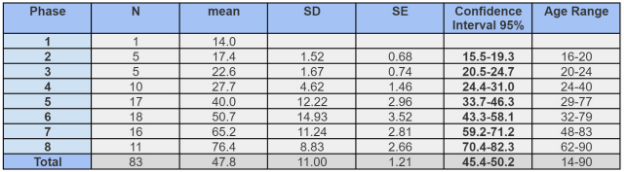

Table 5: Descriptive statistics of phases (females)

Experts using the Skeleton-ID must first identify the phase of rib development and input this along with the sex of the individual. The software then cross-references these inputs with its extensive database, developed from documented cases, to provide a statistically likely age range. This tool is particularly useful for detailed examinations of skeletal remains when precise age estimation is crucial for identification purposes. Since it is based on rigorous scientific research published in peer-reviewed journals, ensuring reliability and precision in age estimation.

REFERENCES

[5] Iscan M.Y., Loth S.R., Wright R.K. (1984), Age estimation from the rib by phase analysis: white males, Journal of forensic sciences 29 (4) 1094–1104.

[6] Iscan M.Y., Loth S.R., Wright R.K (1985). Age estimation from the rib by phase analysis: white females. Journal of forensic sciences, 30(3), 853-863.

Dental morphometric method for Age Estimation

Another integral feature of the Skeleton-ID Biological Profile module is the age estimation tool based on dental root transparency. Lamendin and collaborators developed a method based on the measurement of root transparency and periodontosis [7]. The study was carried out by analyzing 306 uniradicular teeth (incisor, premolar, or canine of the maxilla or mandible) from 208 individuals (135 males and 73 females) aged between 22 and 90 years. They observed no significant differences between sexes and reached the minimum error in the 50-59 age group, while the method’s maximum error was in the 30-39 age group, so its use in younger individuals is not recommended. This method evaluates changes in the translucency of tooth roots, which increase with age due to the accumulation of secondary dentin. Unlike other skeletal methods, this approach requires precise measurement of the tooth, providing a quantitative basis for age estimation that can be highly accurate.

The following distances are measured:

- Root height (RH): Distance between the apex and the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) on the vestibular (labial) and lingual surfaces.

- Periodontal height (HPAR): Distance between the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) and the level of the placement of the periodontium on the vestibular and lingual surfaces.

- Height of root translucency (HTRAN): Distance between the root apex and the point of division between the translucent and non-translucent part. These measurements are also taken on the vestibular and lingual surfaces.

After taking the measurements, the expert will input them in the software and an age estimation will be provided. This technique's foundation is a robust sample size and controlled conditions, as documented in peer-reviewed research, ensuring that the estimates are based on reliable and verifiable data. By combining traditional anthropological techniques with modern computational tools, Skeleton-ID offers a high degree of accuracy and ease of use for professionals in forensic anthropology and related fields.

REFERENCES

[7] Lamendin, H., Baccino, E., Humbert, F. J., Tavernier, J. C., Nossintchouk, R. M., Zerilli, A. (1973). A simple technique for age estimation in adult corpses: the two criteria dental method’, J. Forensic Sci., vol. 37, no. 5, pp. 1373–1379.